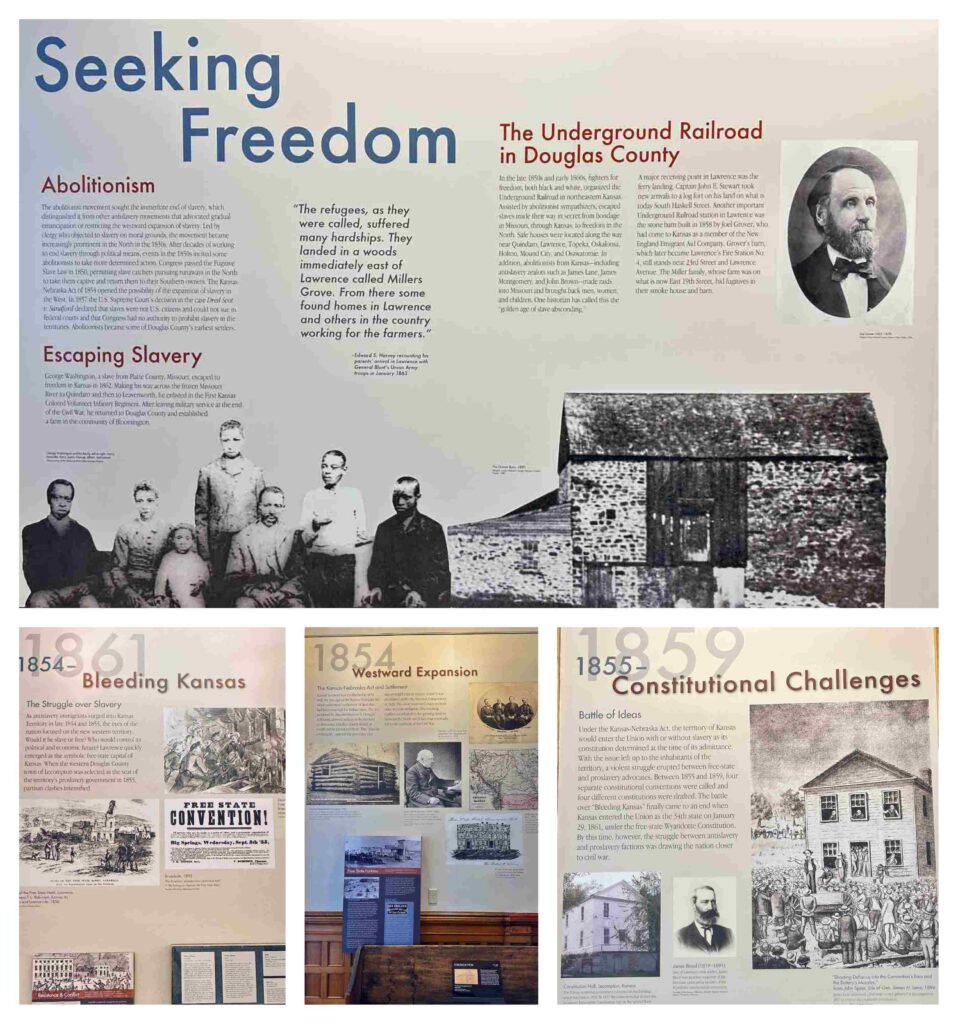

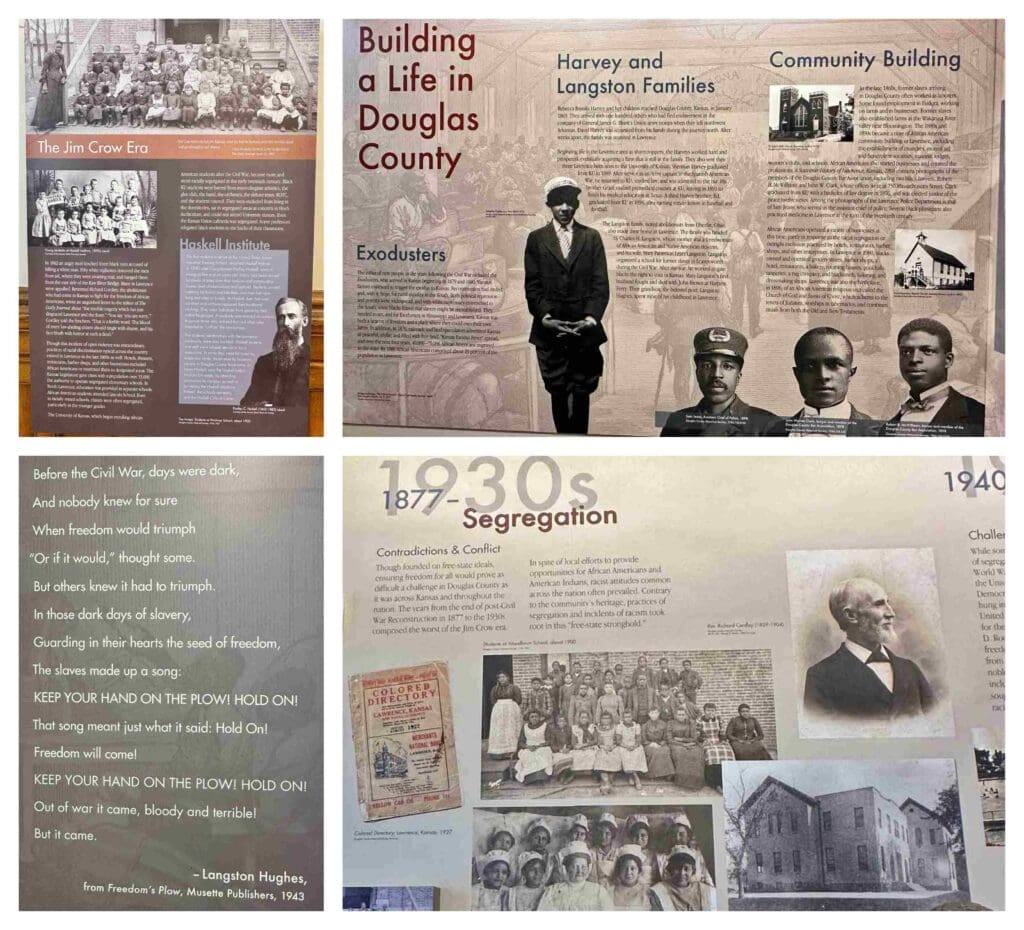

Where Ideals Met the Frontier

Long before the shooting started, tensions gathered like storm clouds on the edge of the Kansas Territory. As the nation wrestled with the expansion of slavery, Lawrence became a destination for those seeking more than land. They sought liberty. Settled by Free-Staters from New England, many came with high hopes and hardened resolve. They built homesteads alongside newly freed Black families and other migrants searching for a better life. But hope was not enough to shield them from the realities of a divided country. Pro-slavery militias from Missouri crossed the border, clashing with Lawrence’s citizens in violent episodes that foretold a much greater war. Many locals remembered those early years as filled with constant fear, as if the whole town lived with one eye on the horizon. In this cauldron of conflict, a fierce identity was born—one that would be tested in ways few could imagine.

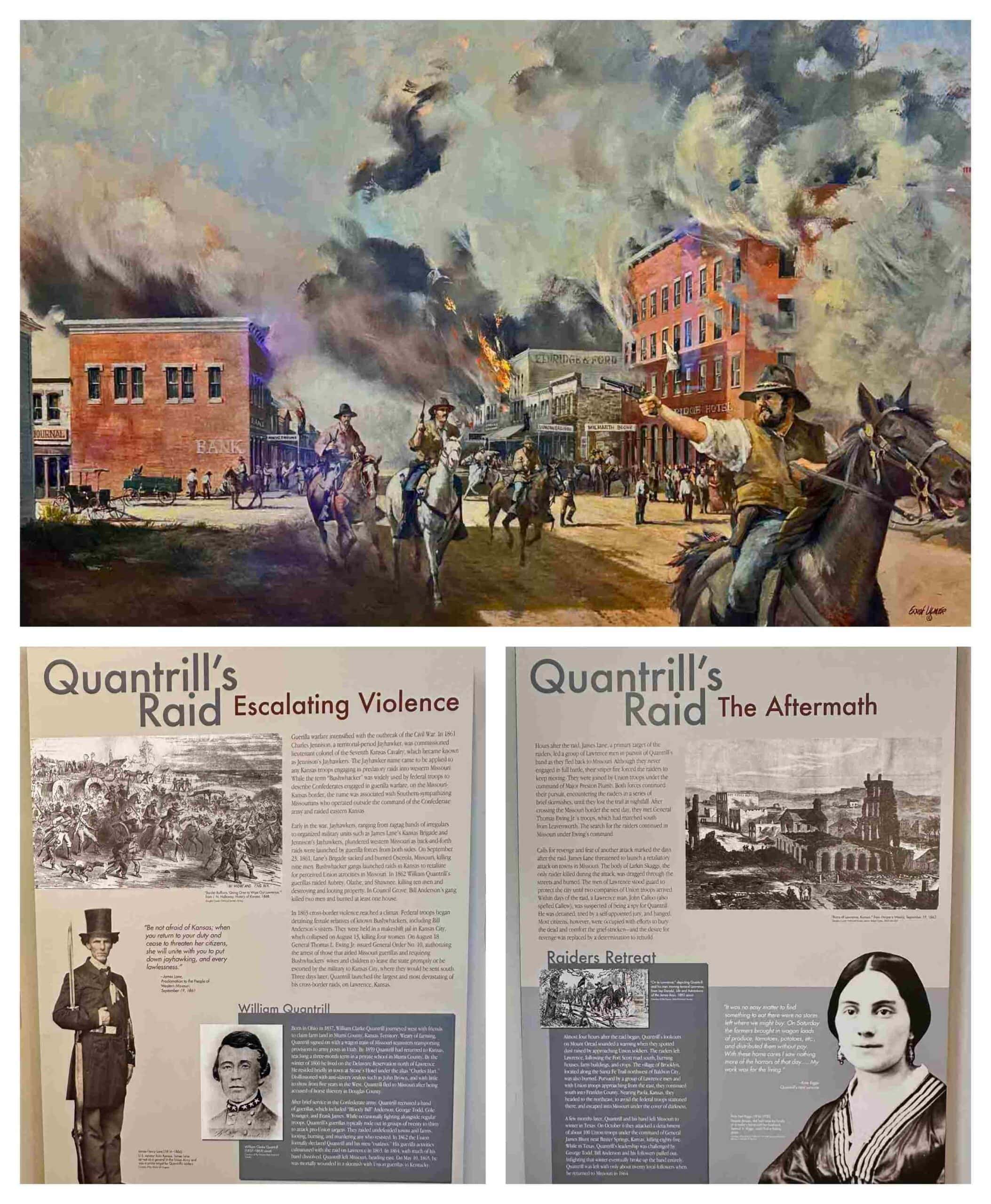

The Day the Sky Fell

At dawn on August 21, 1863, Lawrence awoke to hell. William Quantrill and his band of Confederate guerrillas rode into town with fury in their hearts and torches in their hands. What followed was a massacre—over 150 men and boys killed, homes set ablaze, and the town left in ruins. Survivors spoke of the smoke that hung over the streets like mourning cloth, and of the sound of gunfire that seemed to last forever. It wasn’t just an attack on buildings; it was an attempt to snuff out the spirit of a free town. The raid carved a deep wound into Lawrence’s identity, a trauma that shaped generations. Some say you can feel that morning’s weight in the city’s quiet corners. But Lawrence did not fold. From the ashes of that day rose a fierce determination to endure, rebuild, and remember.

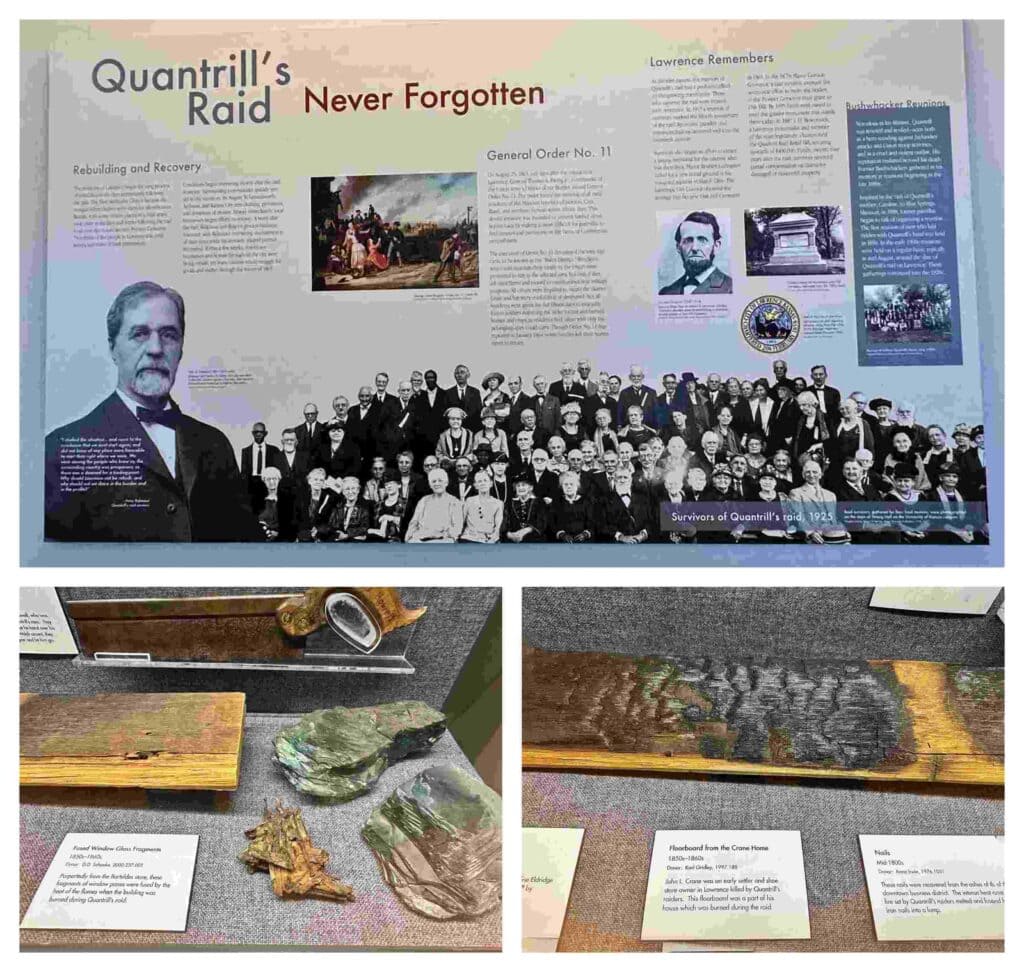

Ashes into Memory

Reconstruction in Lawrence was more than brick and mortar—it was defiance turned into action. Families rebuilt homes on burned foundations, stitched together livelihoods from tattered dreams. The Watkins Museum tells this chapter with artifacts that speak without words: melted glass warped by flame, charred wood once part of a local shop. Each relic captures the fragile courage of a community that chose to stay, to restore what had been lost. Civic institutions rose from the wreckage, echoing the belief that democracy must be defended with arms, archives, and education. The stories told inside the museum today are not just about destruction but rebirth. In Lawrence, memory was not buried under rubble but preserved, curated, and passed forward. This resilience would become the thread woven through every chapter to come.

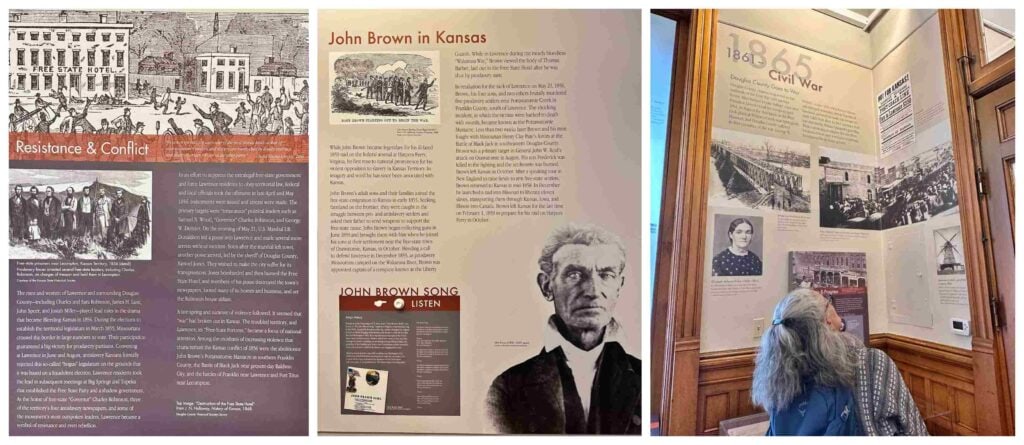

Abolition’s Shadow and a Nation at War

Before the Civil War consumed the nation, the prairie had already been burning. Lawrence knew John Brown not as a myth, but as a man with fire in his eyes and revolution in his step. His raid on Missouri to free enslaved people and the violent stand at Pottawatomie Creek sent tremors through the town. While his methods divided opinion, few in Lawrence doubted his conviction or the urgency of his cause. As the war officially broke out, many of Lawrence’s young men took up arms for the Union, shaped by the skirmishes they had seen in their streets. The town became both a beacon and a battleground, its fate tied to the larger struggle to define America. The echoes of Brown’s defiance and the town’s sacrifices would continue to haunt and inspire long after the final shots were fired.

Barriers and Boundaries in the Aftermath

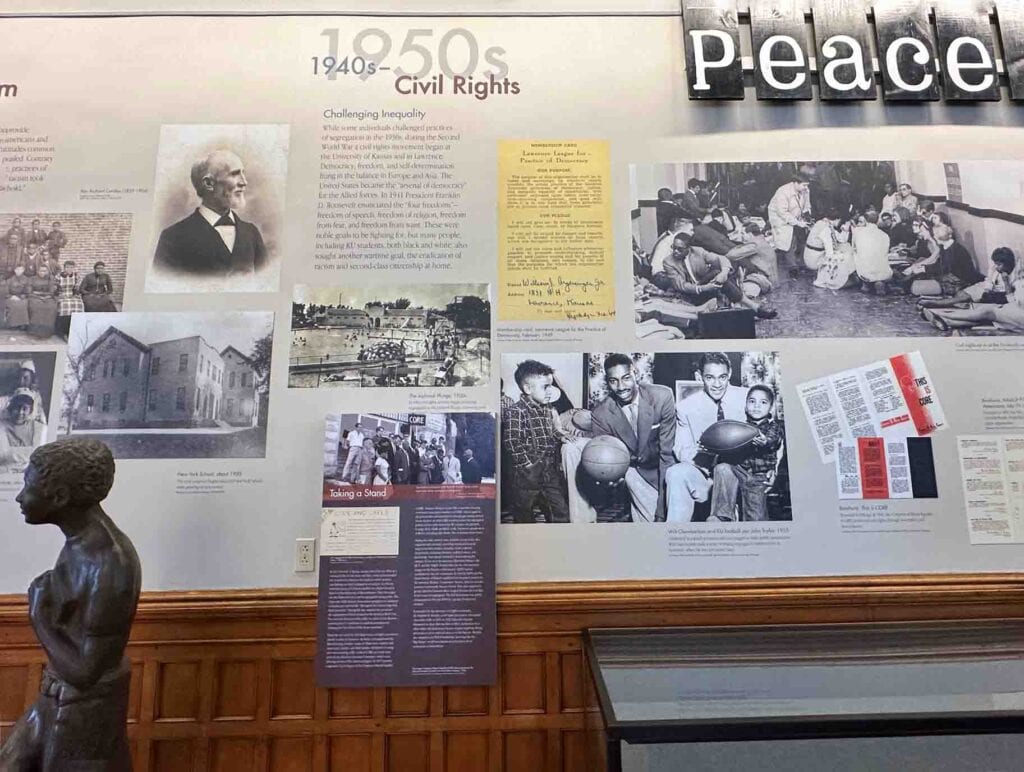

Victory in war didn’t guarantee freedom in practice. After the cannons quieted, Lawrence entered the long, uneven road of Reconstruction. The city’s Black citizens built churches, schools, and businesses, determined to claim a space they had helped preserve. But segregation crept in with quiet cruelty. By the 1920s and ’30s, Black students in Lawrence attended separate schools, and many neighborhoods drew invisible lines enforced by prejudice. Oral histories recall the double lives lived—of resilience at home and resistance in public. The Watkins Museum highlights these overlooked decades, tracing stories of Black excellence alongside the ever-present barriers. Doing so reminds visitors that the fight for justice did not end with emancipation, nor was it confined to courtrooms. It was, and is, lived daily in the hearts of citizens demanding their place in the promise of equality.

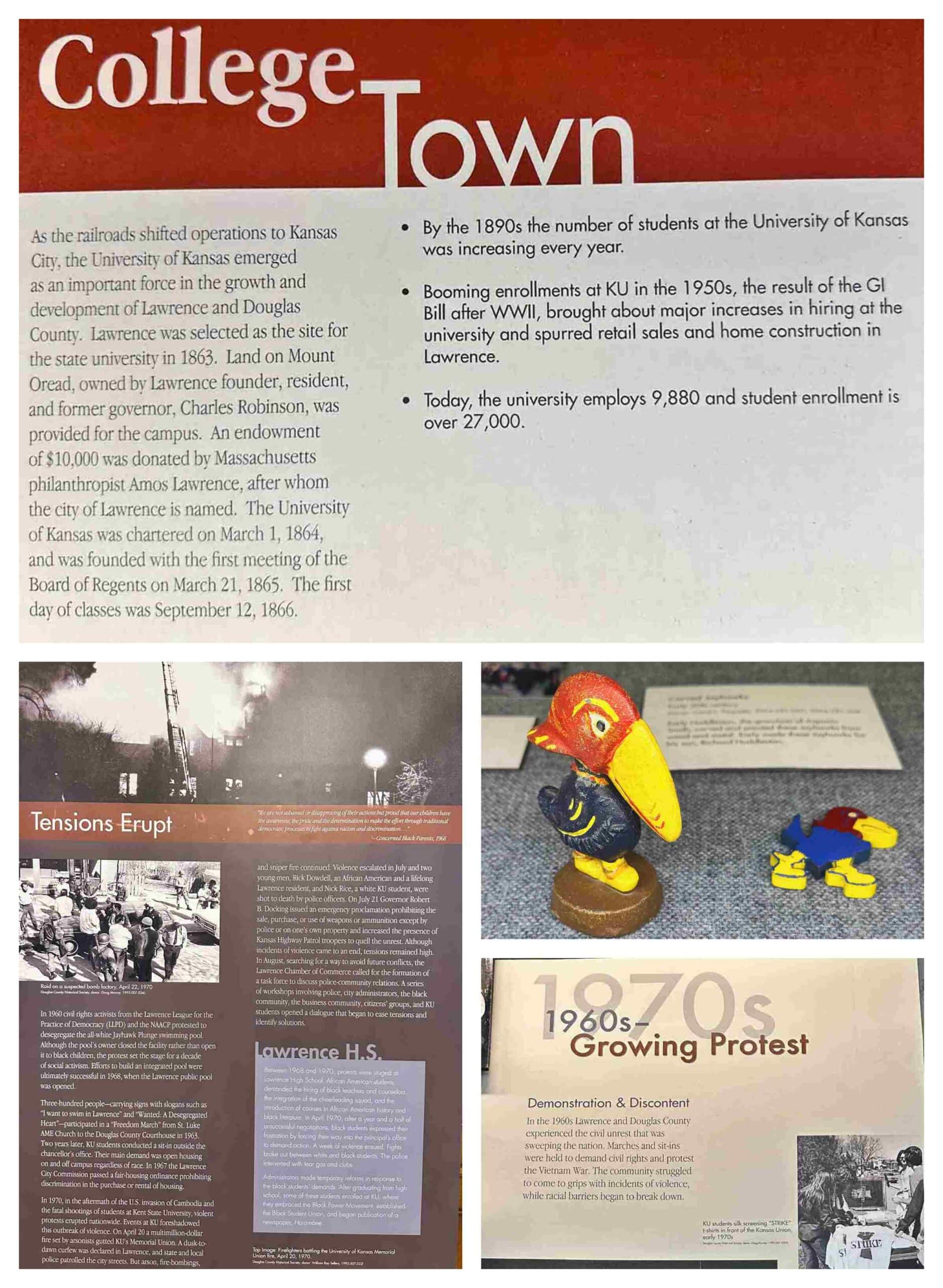

Marches, Megaphones, and a Movement

By the 1950s and ’60s, Lawrence had become a new kind of battleground—this time with protest signs and sit-ins instead of rifles. Students at the University of Kansas joined with local activists to demand civil rights, often facing backlash that echoed the past. Demonstrators filled Massachusetts Street, their chants rising like hymns for change. School desegregation, fair housing, and police accountability became rallying cries. “There was a fire in the youth,” one witness recalled, “but this time it burned for justice, not revenge.” The Watkins Museum of History preserves these voices and radiates that urgency. This era of activism reshaped both KU and Lawrence, bringing policies and perspectives that are still debated today. The civil rights era wasn’t a passing storm—it was a shift in the winds of conscience, and Lawrence stood squarely in its path, with open eyes and raised fists.

From Protest to Progress

The activism of the 1960s and ’70s didn’t fade—it evolved. Antiwar demonstrations and feminist rallies poured into the streets, making Lawrence a hub of progressive thought on the prairie. These movements challenged KU and city leaders, forcing uncomfortable questions and courageous conversations. Through it all, the town grew—not just in size, but in self-awareness. Today, Lawrence wrestles with its past while daring to dream forward. The Watkins Museum of History stands at the crossroads of remembrance and reflection, guiding new generations through the stories that shaped them. In its quiet galleries and dynamic exhibits, visitors are invited to see what happened and why it still matters. Because history, especially here, is not something we leave behind. In Lawrence, they carry, question, and continue to grow together.

Thanksa lot for the post. Want more.

Glad you enjoyed it.

By Jeff & Crystal, thank you for this post. Its very inspiring.

We appreciate the feedback.

By Jeff & Crystal, thanks so much for the post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Glad you enjoyed it.

Thank you ever so for you post.Much thanks again.

You are quite welcome. We are glad you enjoyed it.

First time to your posts. Jayhawk history ftom the Watkins museum was very imformative. Thank you both.

We are glad you enjoyed it. We hope you come back often.

Mister Skaggs the Quantrill member was not hung the day after the raid. he was killed the day of the raid. He was drunk and did not leave with the main body. He was trapped and killed and his body was hung after he was killed.

Thanks for clarifying.