Arriving during peak fall foliage, the mountains trade summer green for gold, and the air feels thinner and sharper with every breath. This is the Great Basin, and from the first moments, it feels less like a destination and more like a pause. Aspen leaves shimmer above us, and the quiet is so complete we notice our own footsteps. We are here together, moving slowly, letting the landscape set the pace.

The season shapes everything. The light is softer and the air cooler. The colors feel earned rather than staged, tucked into canyons and high valleys. Standing there, we already sense this place will stay with us long after the drive pulls us back toward lower ground.

What Makes This Place Different

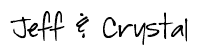

What sets this landscape apart is not immediately visible, but it shapes everything we experience. This region belongs to a massive interior drainage system where water never reaches an ocean. Rain and snow fall, streams form, and then the water disappears into desert flats or dry lake beds. Nothing flows outward. Everything stays.

Mountain ranges rise abruptly from broad valleys, running north to south like parallel ribs. Each range captures moisture, leaving the next valley drier than the last. Over time, this pattern creates sharp contrasts in elevation, climate, and vegetation. We sense how enclosed the land is, shaped inward rather than outward, defined by accumulation instead of escape.

This geography explains the sense of isolation we feel. It also describes the resilience required to live here. The land is self-contained, requiring attention to subtle changes in elevation, water, and weather. Understanding that makes every quiet mile feel intentional rather than empty.

Indigenous Presence and the Deep Past

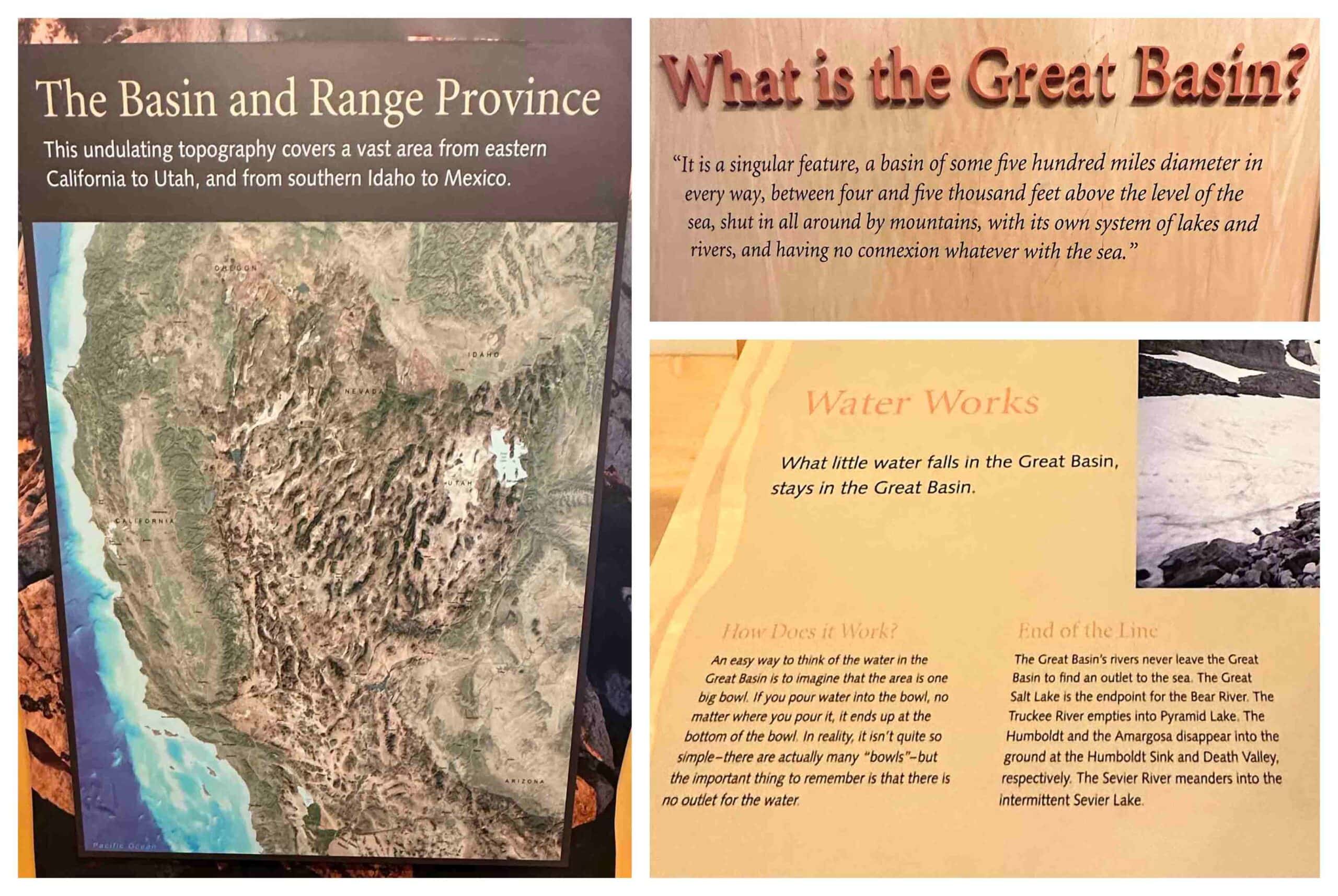

Long before modern borders or park boundaries, this region supported Indigenous communities who understood its constraints and possibilities. Among them were people connected to the Fremont culture, whose presence is traced through rock art, dwellings, and tools found across parts of the Great Basin region. They lived in a space between hunting and farming. Their methods adapt flexibly to changing conditions rather than imposing change on the land.

Seasonal movement was essential. Groups traveled between valleys and higher elevations, following food sources such as pine nuts, small game, and cultivated plants. Water dictated everything. Knowledge of springs, weather patterns, and elevation was passed down carefully, refined over generations.

Their relationship with the land was practical and deeply informed. Survival depended on restraint and observation, not dominance. Walking through this landscape now, we are aware that our brief passage rests on thousands of years of careful adaptation.

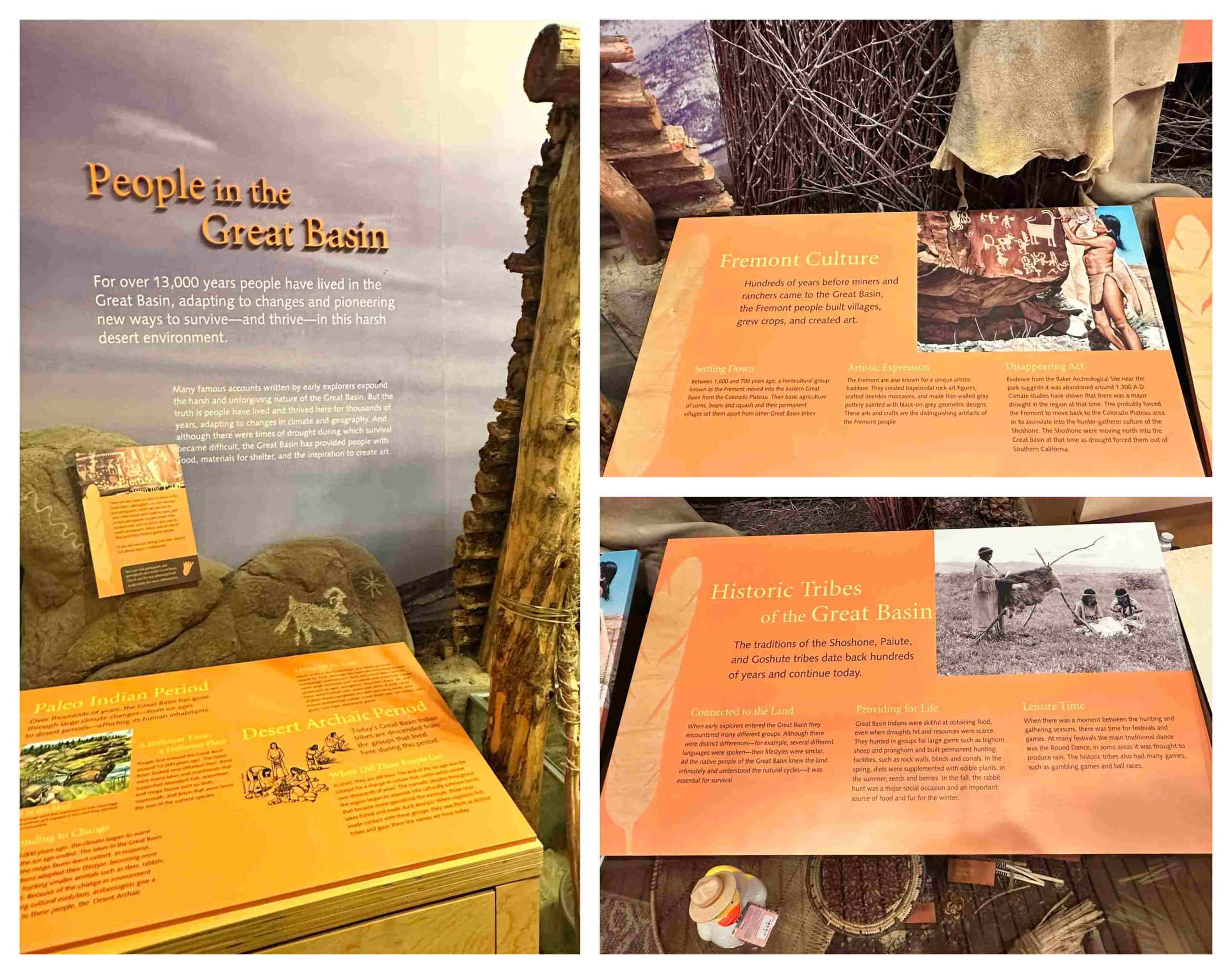

Immigrants and a Changed Landscape

The arrival of European American settlers in the nineteenth century altered that balance. They were drawn by mining prospects, grazing land, and westward expansion. These newcomers imposed fixed boundaries on a landscape that had long resisted them. Towns rose and fell quietly, leaving behind traces that still surface in the surrounding valleys.

These outsiders struggled against isolation, harsh winters, and limited resources. Many did not last. Yet roads, trails, and altered land use patterns remain. They form the framework of access we rely on today. The story here is not one of triumph, but of persistence shaped by challenging geography.

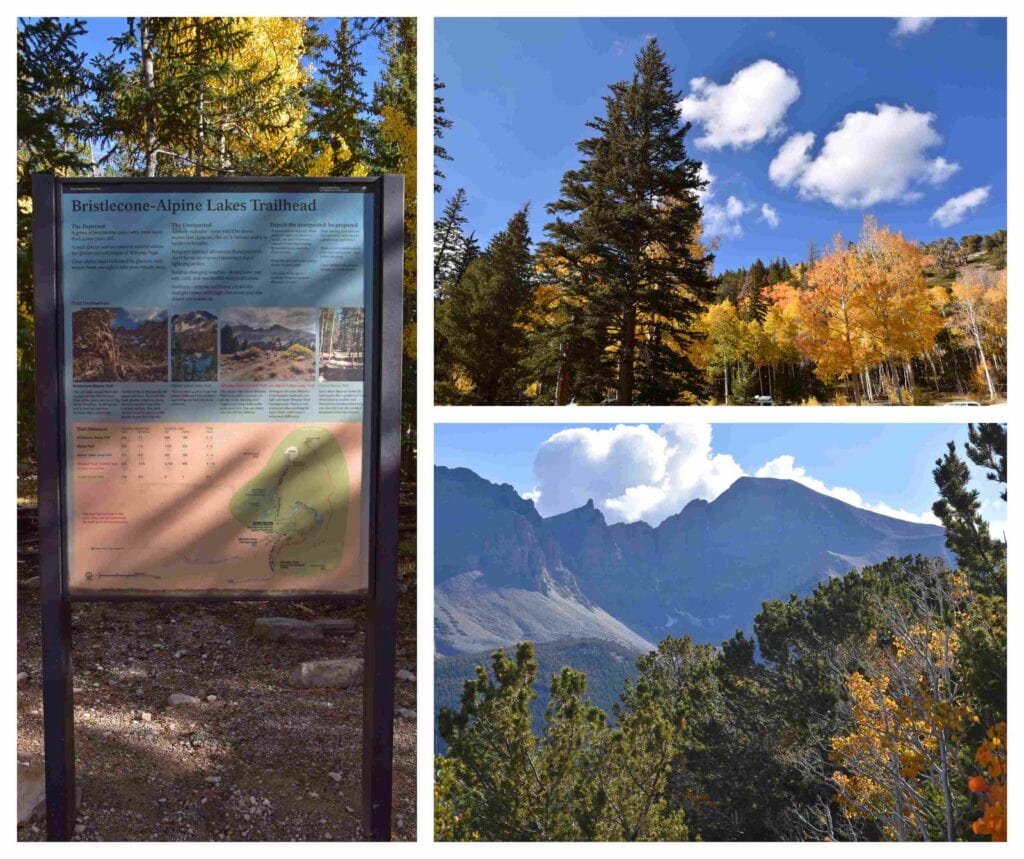

The Drive to Wheeler Peak

The road climbing toward Wheeler Peak feels like a gradual negotiation with altitude. As we ascend, the landscape tightens and cools, forests closing in around the pavement. The parking area sits at roughly 10,000 feet, and by the time we arrive, the temperature has dropped noticeably.

The shift is immediate and physical. Breathing takes more intention, and the exposure can feel unsettling for anyone sensitive to elevation. We move deliberately, as the environment asserts itself. On the ascent, the view to the right is sheer drop-offs. It is a beautiful drive, but one that demands respect and awareness.

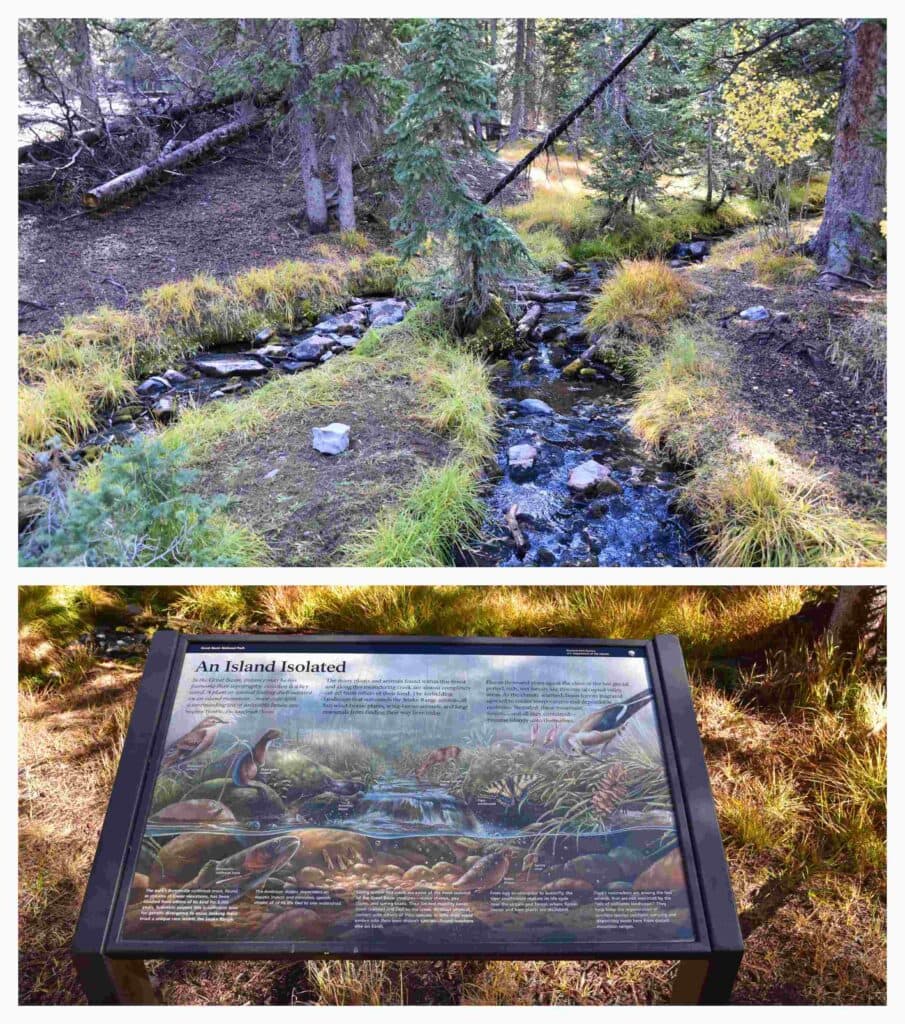

It becomes clear that these mountains function like an island. Native plant species survive here in relative isolation, shaped by cooler temperatures and lingering snow. Over time, this separation allows unique communities to persist. They adapt independently to thin air and short growing seasons. Up here, we feel that isolation is not emptiness, but protection. It’s a reminder that distance and difficulty have helped preserve what still feels rare and intact.

Hiking the Bristlecone Trail

With limited time, we choose a path that leads into the surrounding natural beauty. The Bristlecone Trail carries us upward through a landscape that feels suspended between eras. Ancient trees cling to rocky soil, their twisted forms shaped by wind, cold, and time. Each step feels deliberate. The air is cooler here, thinner, and the silence presses in gently, encouraging us to slow our pace and take in what surrounds us.

As the trail opens up, the terrain reveals something unexpected. Off in the distance, tucked against the mountain, we see the glacier, the southernmost one in the United States. It feels almost out of place at first, a quiet remnant of a colder world surviving against the odds. Standing together, we let that sight settle in, aware that we are witnessing something both fragile and rare.

The hike becomes less about reaching a destination and more about perspective. Between ancient trees and enduring ice, the trail reminds us how time behaves differently at elevation. We move through it carefully, aware that simply being present here is part of the experience.

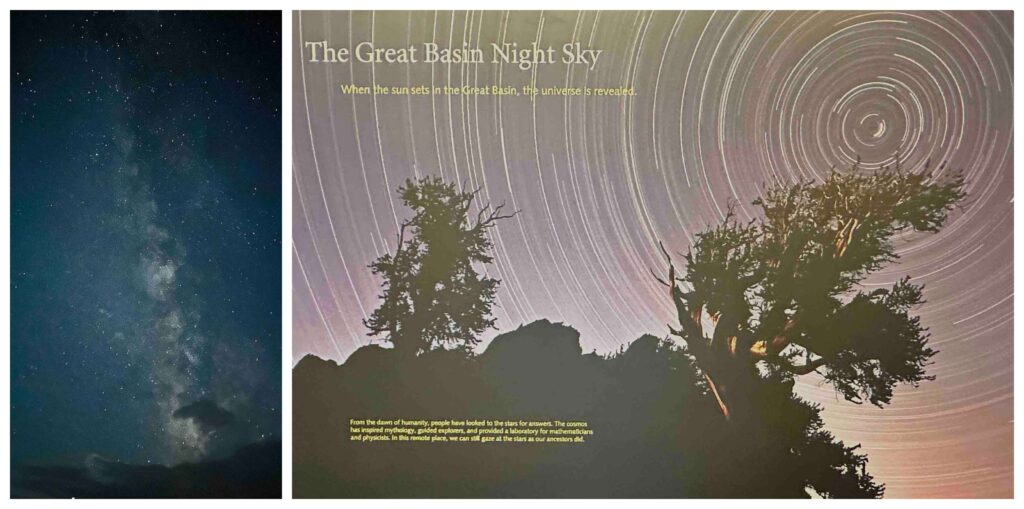

Great Basin and the Night Sky

After dark, Great Basin reveals one of its greatest gifts. With almost no light pollution, the sky opens fully. I make my first attempt at night sky photography, adjusting settings and hoping for the best, but the camera quickly becomes secondary.

What holds us is the sheer number of stars. We stand together, looking up, recognizing patterns we have not clearly seen since our youth. The sky feels close and immense at the same time. It is less about capturing an image and more about remembering how vast the world can feel when darkness is allowed to exist.

Planning Your Visit

Visiting Great Basin National Park requires a bit of forethought. There is no entrance fee, and the park is open year-round, though weather can limit access at higher elevations. The park sits in eastern Nevada, far from major cities, so fuel and supplies should be planned.

Higher elevations mean cooler temperatures, even in fall, and sudden weather changes are common. Altitude can affect visitors differently, so pacing and hydration matter. For those willing to prepare and slow down, the reward is a place that offers space, history, and night skies that still feel endless.

If this place sparks something familiar or awakens a little curiosity, we hope you pass that feeling along. Share this story with friends who crave quiet roads, dark skies, and landscapes that still feel undiscovered. Some places are best experienced slowly, and even better when the invitation comes from someone who understands that not every great adventure needs crowds to feel extraordinary.