American history is filled with events large and small, but some created a reverberation felt throughout the country. While the Civil War had legally brought an end to slavery, it did not prohibit the inequality of segregation. Black people were told they were free, but real life didn’t represent this change. Jim Crow laws had created barriers that precluded black Americans from enjoying the same opportunities as whites, especially in the southern half of the country. Leveling the field would require a fight that led to the Supreme Court.

Brown v. Board Museum

We’ve visited Topeka many times, but have somehow missed the Brown v. Board of Education Museum. This national historic site is located at the Monroe Elementary School. The school was built on the land of one of Topeka’s founding fathers, Jacob Chase. A parcel of Chase’s land was purchased by John Ritchie and his wife, Mary. The couple was abolitionists who helped aid the Underground Railroad. In 1868, three lots of Ritchie’s land were purchased by the Topeka Board of Education. Here they constructed a school for black children. This building would eventually be razed and a new school was built with the addition of 10 more lots. The elementary school took its name from the street that borders the property, where it would operate until 1975.

Learning From the Past

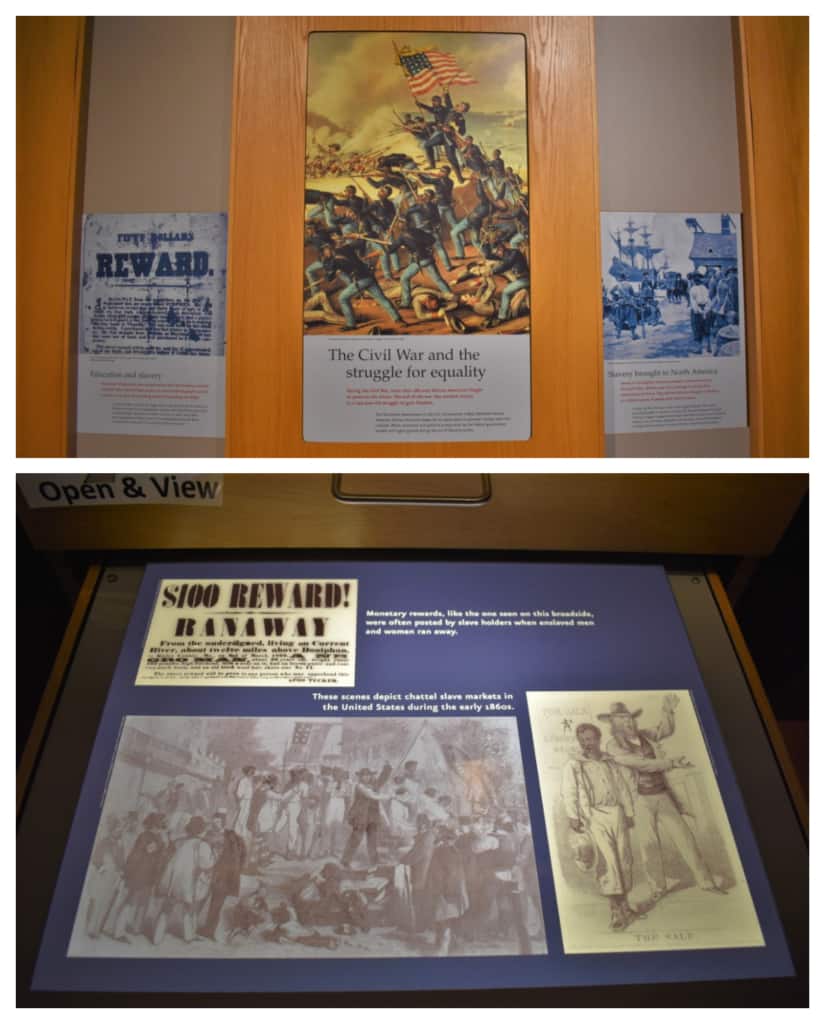

While there are differing viewpoints on the reasons for the Civil War, the issue of slavery played a central role. On farms and plantations throughout the southern half of the nation, enslaved people were prohibited from their rights. Of course, slavery wasn’t limited to these large agricultural estates. Households were also commonplace settings to find forced labor. Our excursions, to cities in the south, have opened our eyes to the expansive use of enslaved people in many parts of our country. Their stories speak volumes about how the mainstream population treated black people as property.

Not Equal Rights

It is estimated that less than 2% of US citizens owned slaves. While this number seems small, it represents about 630,000 people. An 1860 census showed almost 4,000,000 slaves were held in 15 states and territories. Many would automatically picture the deep south, but there were also slaves held as far north as Delaware. At the same time, nearly 400,000 free black people lived in the southern states. While many were successful business owners, they were not treated as equals. The task of freeing the enslaved people was an enormous undertaking that divided a nation.

What Now?

In 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation announced freedom for African Americans in the rebel states. The country was nearing the third year of the Civil War and President Lincoln was looking to renew their passion for the fight. While this move was an important step, it did not impact slavery in the Union States. For it to be effective, the enslaved would have to escape the control of their owner. As the end of the war drew near, many were concerned that the proclamation would be seen as simply a war measure. Lincoln pressed Congress to pass the 13th Amendment, which would ban slavery in all U.S. states and territories. While the law could grant freedom, social cultures would be harder to change.

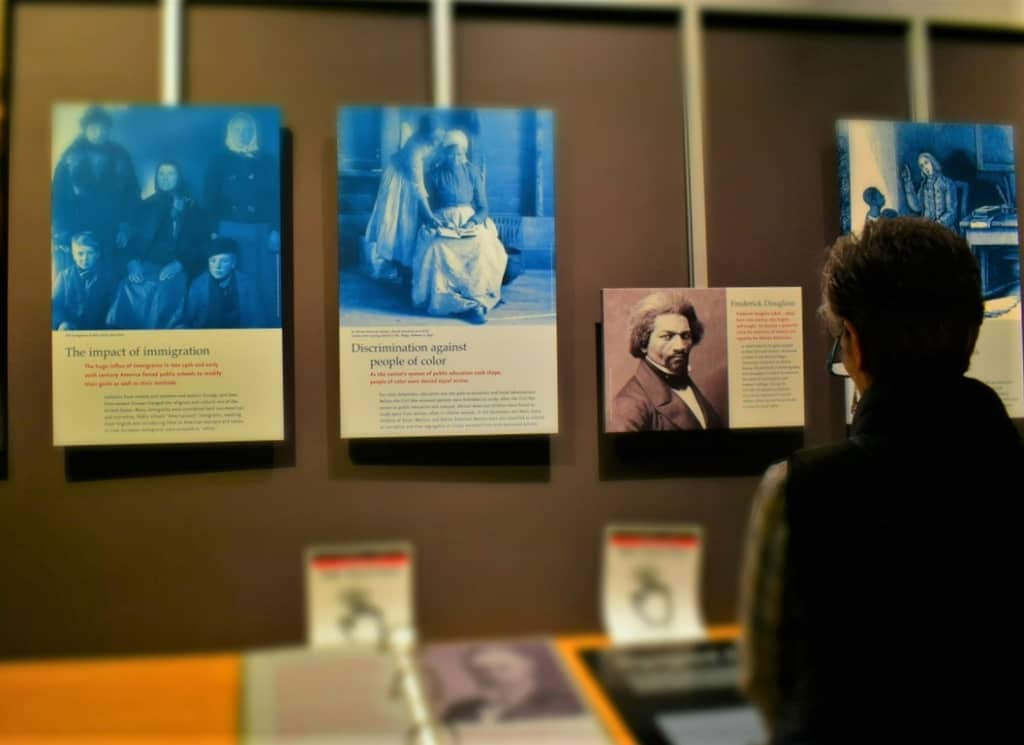

The Long Road Forward

The task of leveling the field had only begun and Black Americans were finding new barriers. Peonage, which shackled black workers with debt through oppressive loans, was outlawed in 1867, so new ways had to be found to keep blacks segregated. The establishment, in most southern states, found replacements with Jim Crow laws. These local and state laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities, including schools. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled that this form of racial segregation was not a violation of the Constitution. Their stipulation was that each race would have facilities that were equal in quality. This approach became known as separate but equal.

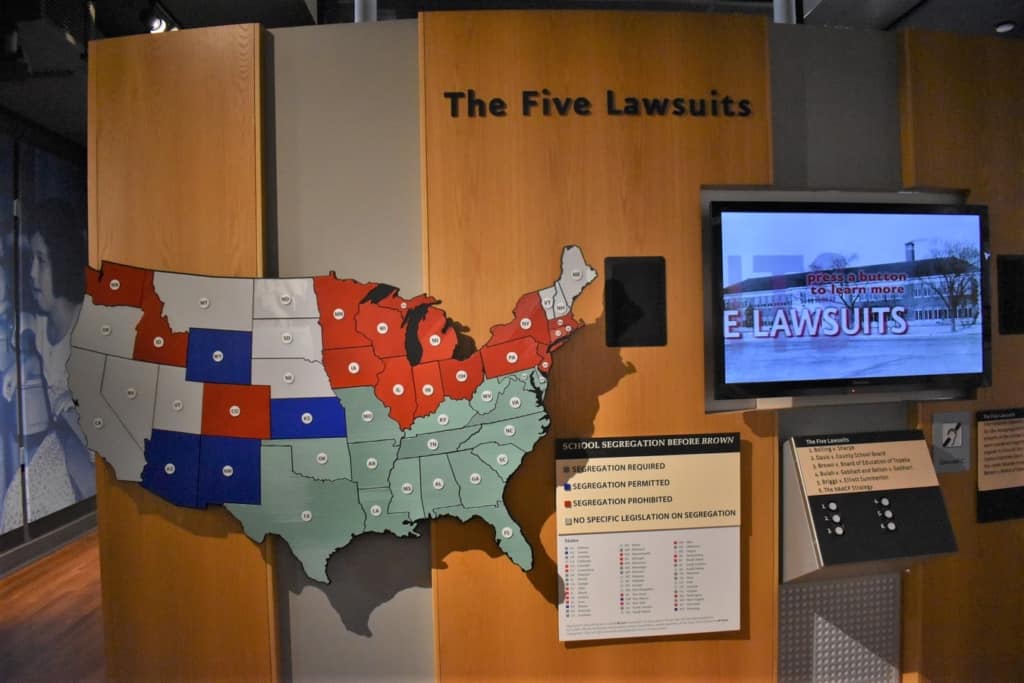

The Lawsuits

Fast-forward to the 1950s, and black people were still facing racial segregation six decades later. The NAACP was working to make changes to these laws, by showing how they were not being applied in an atmosphere of equality. Public facilities, schools, and other sites were far from equal in quality. It was time to integrate the American school system, but not without a fight. In 1951, a black Topeka family, named Brown, attempted to enroll their daughter into the elementary school that was closest to their home. The request was denied and she was forced to ride a bus to the segregated black school, which was farther away. Joining with a dozen other families, they filed a class-action lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education. The District of Kansas U.S. District Court came back with a verdict against the families.

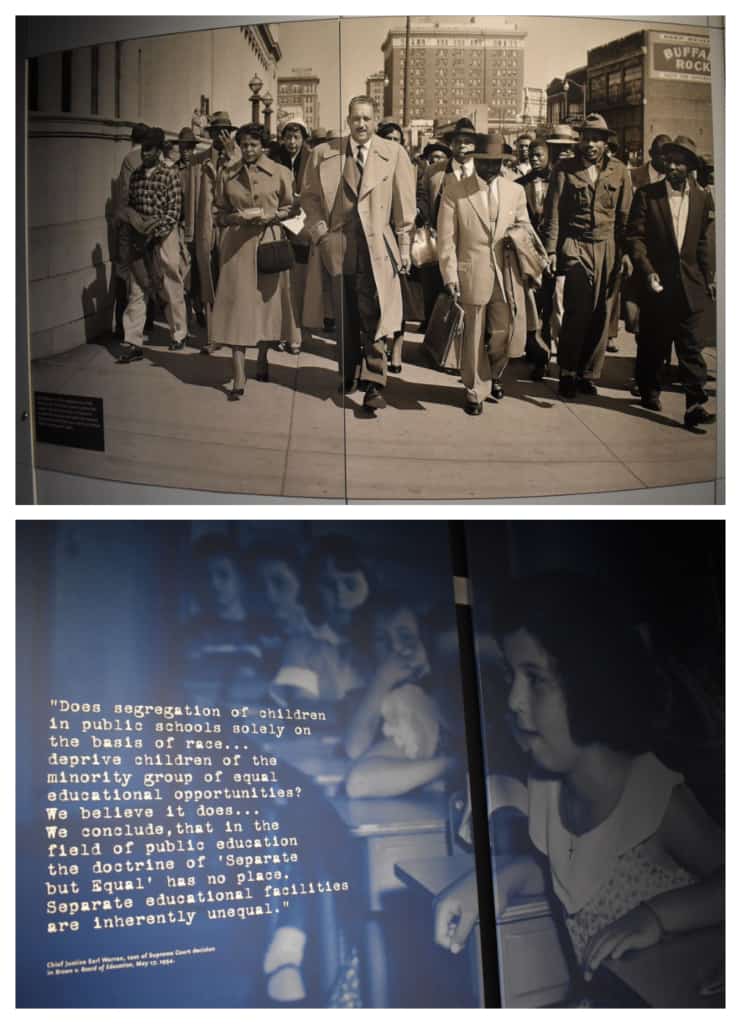

Leveling the Field

The Brown family was not to be dismayed. Represented by the chief counsel for the NAACP, Thurgood Marshall, they pushed the case forward to the Supreme Court. The question posed to the court was whether any separated educational facilities could really be equal. The justices determined, in a 9-0 ruling, that it was not possible. Therefore, racial segregation could not be part of the education system. While it was a huge win toward equality, it did not lay out a path to resolve the issue. We had learned about some of the difficulties in implementing this new decision during a visit to Central High School, in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Facing Discrimination

While many Americans cheered the landmark decision, it was not well accepted in much of the South. The integration of schools moved slowly when it moved at all. The border states did accept the change and moved toward integration, but this was not the case in the Deep South. Resistance was stiff and in many cases, no movement was made. A Massive Resistance strategy was implemented to block desegregation by any means. The removal of black educators and staff was used to limit the ability to gain insight into how far-reaching the fight had seeped into the southern education system. When other attempts failed, entire school systems were shut down to block integration.

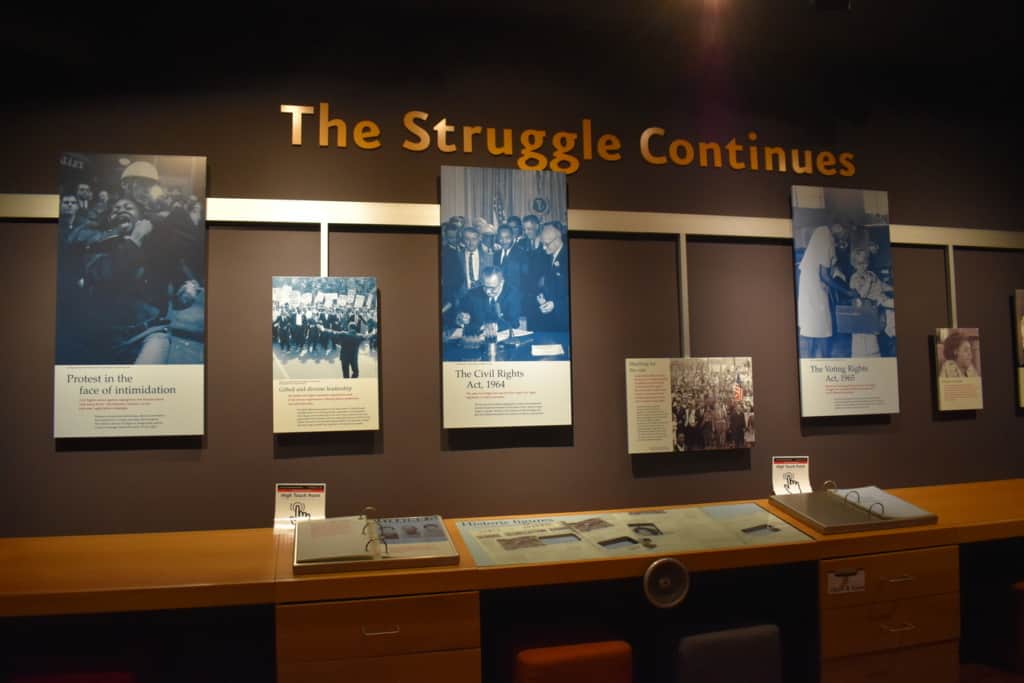

The Fight’s Not Over

The fight for leveling the field in education was only one facet of the inequality faced by Black Americans. Even after the decisive victory of Brown v. Board, there remained a large gap between the races. Employment and housing opportunities were filled with unfair practices. As black people migrated to the north, many new housing projects were designed to be racially restrictive. Equal but separate was continuing, but hidden by the use of restrictive clauses and legal jargon. From this atmosphere, heroes arose. While the name Rosa Parks is easily recognizable, too few know that only months prior Claudette Colvin had been arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, Alabama.

Looking Toward the Future

The Civil Rights Movement, while met with stiff resistance, put a chain of events into action that could not be undone. Each victory brought new freedom, while each defeat renewed the drive for change. The media provided documentation of the violence and discrimination faced by Black Americans on a daily basis. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act would outlaw discrimination on the basis of color, race, religion, or sex. The fight for true equality continues today. It is important to support the sites, like Brown vs. Board of Education, that remind us of the importance of learning from our past.