Being at the forefront of the national news is something that many cities would dream of, but not when it is due to public strife. While the conflict at Central High School was 60 years ago, we still see some of the struggles continuing today. Little Rock, Arkansas may have been the backdrop for this particular integration crisis, but it was by no means the only stage where the drama was being played out.

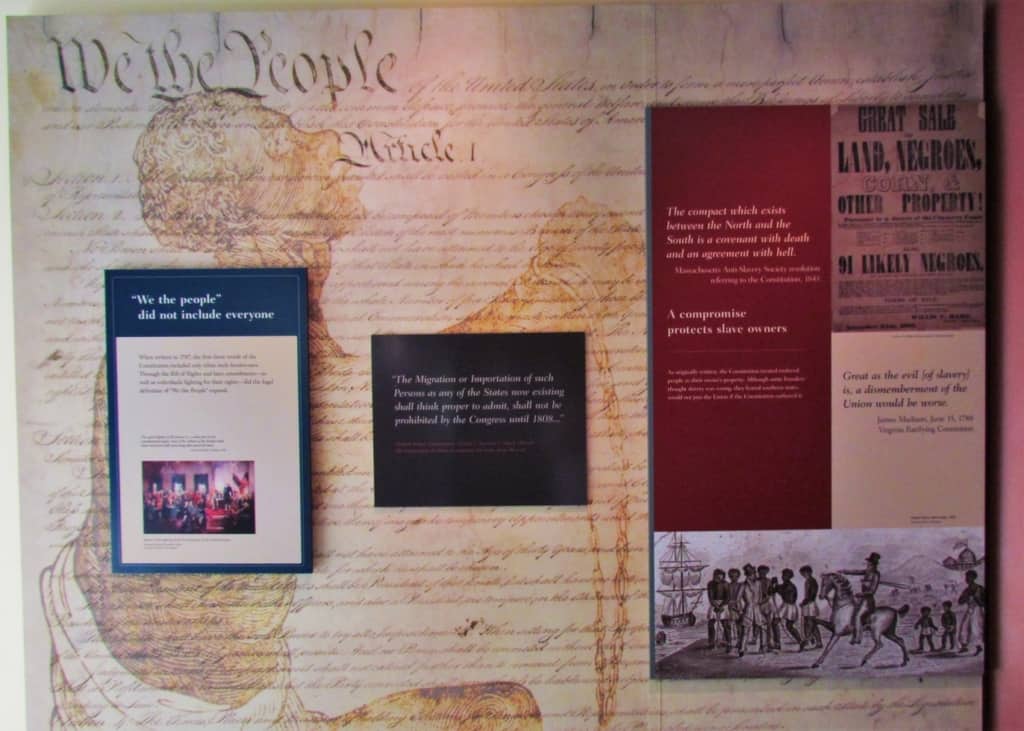

Free, But Not Free

The Conflict in Little Rock originated with the Supreme Court ruling that states could not legally separate black and white students in different schools. Being from Kansas, the Brown vs. Board of Education was well known, so a visit to Central High School was not to be missed. In 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment, which addressed citizenship rights for the recently freed slaves, was added to the U.S. Constitution. This was hotly debated by many of the states that had been part of the Confederacy. In an effort to further define the intent of the law, in 1896 racial segregation was allowed, as long as it was “separate but equal”. It would take until 1954 for this policy to change. The school case in Kansas would be the impetus for change, but it would be met with mixed resistance.

Little Rock Nine Change Schools

With the Supreme Court calling for desegregation of the nation’s public schools, the battle-lines were drawn. In 1957, the NAACP registered nine black students to begin attending Little Rock Central High School. At the time of its construction in 1927, Little Rock Senior High School was deemed the most beautiful, largest, and expensive high school in the nation. The name changed in 1953, but enrollment continued to be restricted to white students. The original plans for integration were for a full scale approach in all grade levels, but this was reduced to focus on a single school. The hesitancy and slow movement of the school board to initiate integration was another factor in the conflict that was brewing.

Setting The Scene For Conflict

With the upcoming school year bringing the possibility of an integrated classroom, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus put into action motions that would bring the conflict in Little Rock to the forefront of national attention. Several segregationist groups were planning protests at Central High School, in an effort to block the black students from entering. The governor deployed the Arkansas National Guard to assist the blockade. Photos showing the line of soldiers blocking the entrance made national news. The nation held its collective breath, as it waited to see how President Eisenhower would react. The president warned Governor Faubus not to defy the Supreme Court’s ruling. The mayor of Little Rock, Woodrow Wilson Mann, requested President Eisenhower send federal troops to assist in enforcing integration.

The morning of September 23, 1957 dawned with an air of tension hanging heavy around the school. Over 1,000 whites had assembled at the school to protest the integration. The nine black students, who would be labeled the Little Rock Nine, were escorted past the angry mob by Little Rock police officers. Violence broke out and the students were removed for their protection. The crowd’s actions propelled President Eisenhower to order a 1,200 man Army division to escort the students into the school, on the following day. This move escalated the showdown between the president and Arkansas Governor Faubus, who questioned the authority of the federal court system.

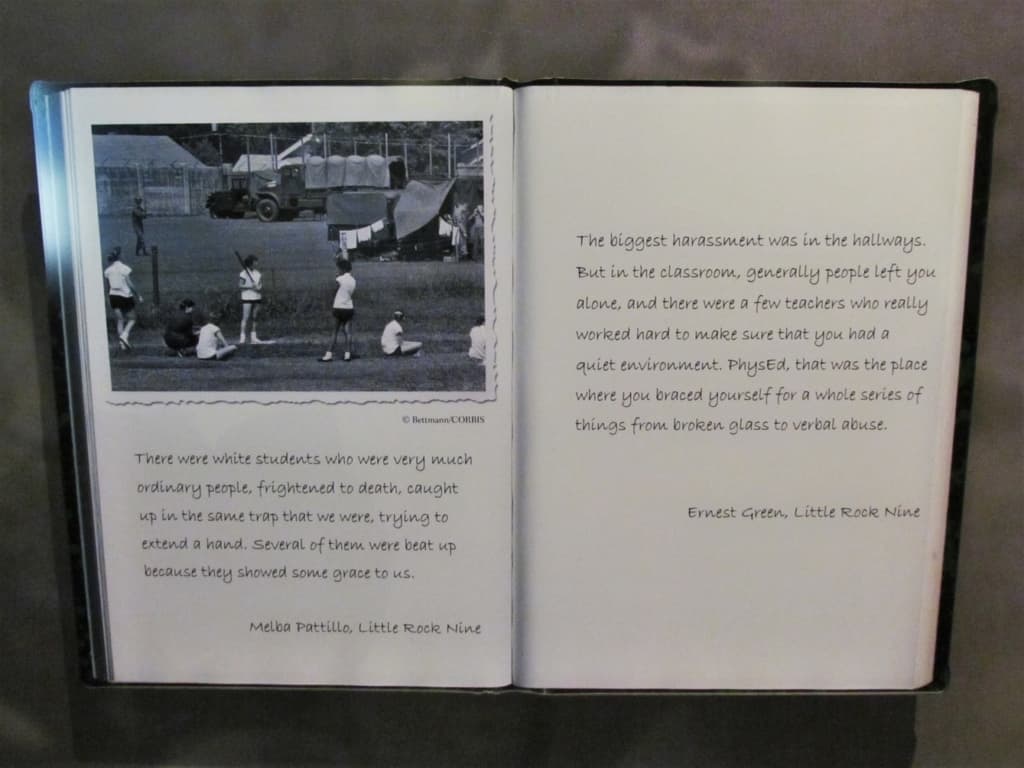

Surviving Day To Day

The Little Rock Nine would spend day after day facing the wrath of those against integration. Physical and verbal abuses were commonplace on a daily basis. One of the students had acid thrown in her eyes. Another was trapped in a bathroom stall, while white students dropped pieces of burning paper from above. The nine were warned not to fight back even though they would face a lot of abuse. By the end of the school year, the governor was creating a new way to fight desegregation. He ordered the closure of all four public high schools in Little Rock. Requiring a referendum to allow this action, he urged voters to pass it. The plan would be to reopen the schools as private institutions, so that they could once again be segregated. Faubus won the referendum, and the 1958-59 school year would become known as the “Lost Year”.

Does Time Bring Change?

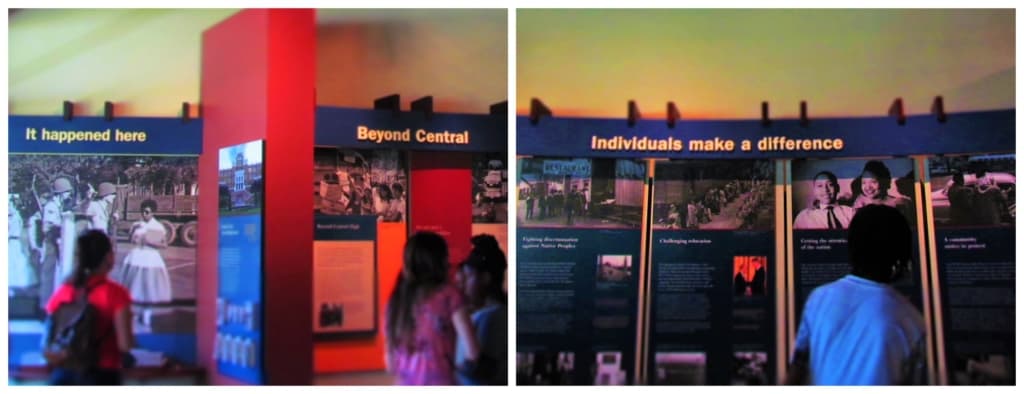

Scenes similar to those in Little Rock were played out across the south. Over time desegregation made a lasting effect on the public education system. These days, Central High School continues to serve its purpose, while the museum dedicated to the events is located nearby. Tours must be scheduled of the the school, but the museum is available to all, during its regular business hours. The Conflict in Little Rock would eventually lose its place on the front page, but the impact has resonated throughout the nation.

These days students of all backgrounds are supposed to be able to attend public schools without fear of persecution, but is that really the case? Too often we are seeing stories in the news about bullying. Many of these cases are leading up to our children lashing out in retaliation. How have we gotten so far, yet still seem to have a long road in front of us? It is sites like the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site that remind us how important tolerance is to the human spirit. We hope you all have an opportunity to visit places like this, as it reminds us how important we all are to each other.

Sharing is Caring!

I enjoyed your article about Central High. I remember like it was yesterday actually going down to see the troops. At age 7, I had no idea of what was going on but my mother knew it was significant and important for us to see what was going on.

Like most historic events, the participants have no idea of the significance until later. It is truly an educational moment in our country’s history.

But you didn’t finish the story. All of this culminated in the Little Rock School District coming under receivership by the State of Arkansas for 5 years due to failure of the system. The system is now predominantly segregated with most of the white students fleeing to Bryant and other school systems or private schools. Isn’t that as much a part of the legacy as the story you portray?

The article we developed was based on the period of time that we learned about during our visit to the national museum.

I graduated from Little Rock Central High and also taught there. Many of my family attended the school. I always found that a true story was a complete story that hid no facts regardless of their slant on whatever theme one was trying to convey. Unfortunately, it appears that censorship is still alive and well here. I posted a comment on this post and found it removed. Not because it was not honest but because it was not slanted in the correct direction. The legacy of Central HIgh continues to this day and we all know what that is. The system is no longer integrated but remains predominantly segregated after being under receivership of the State of Arkansas for five years for failure. Surely that fact can be reflected in it’s legacy as an honest portrayal of the system as any other.

Your comment, like every other one posted, must be approved before it is visible on our website. I try to do this approval process each morning, so sometimes there is a lag on when they appear. We try to have no “slant” to our posts. Our website is designed to encourage people to travel. Get out and see things you have never experienced. We believe that by doing that we continue to educate ourselves about the world around us.