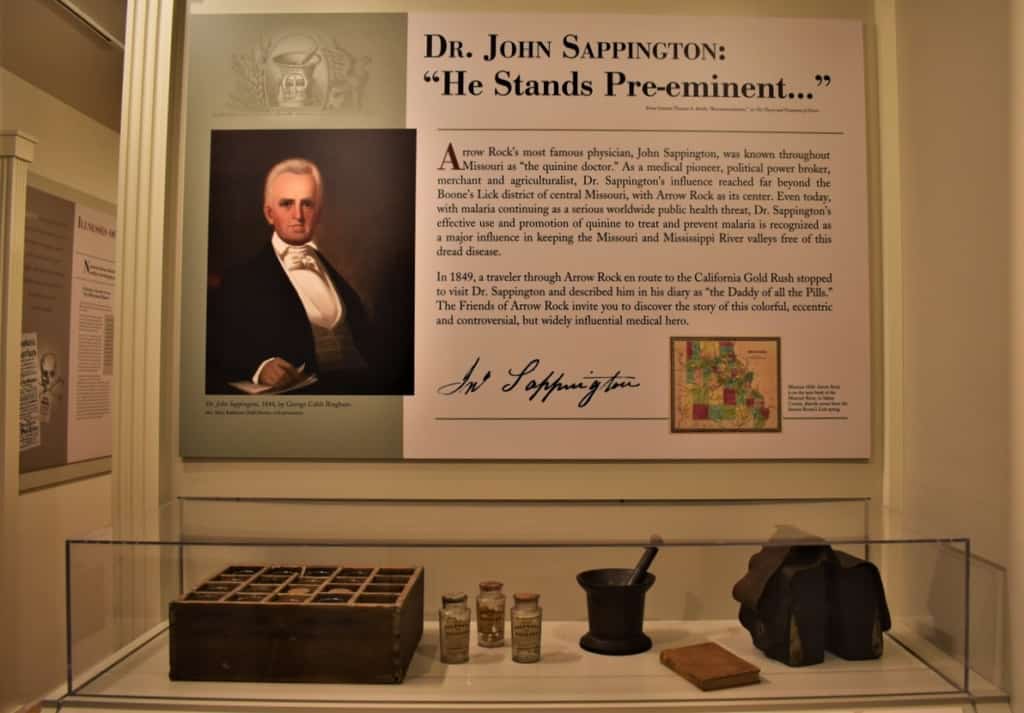

It has been said that history tends to repeat itself. During a visit to Arrow Rock, Missouri, we stumbled upon a small museum dedicated to the life of Dr. John Sappington. His name was unfamiliar to us, but as we explored the space, we soon realized the important role he played in history. This little known pioneer doctor would be key in stopping the spread of malaria across the new western frontier. Our visit took place during the midst of the Covid pandemic, which finds us hoping that another great mind will unlock the key to stopping the spread of this current plague.

Heading West

John Sappington was born in Maryland and came from a medical background. His father had studied medicine in Pennsylvania and became a physician. During his childhood, the family moved to Nashville, Tennessee. That is where he and his brothers would study medicine with their father. The time period was right around the beginning of the 1800s. With the frontier expanding at a frightening pace, doctors were in high demand. A chance meeting with Senator Thomas Hart Benton would lead to Dr. Sappington’s relocation to central Missouri.

Trying Times

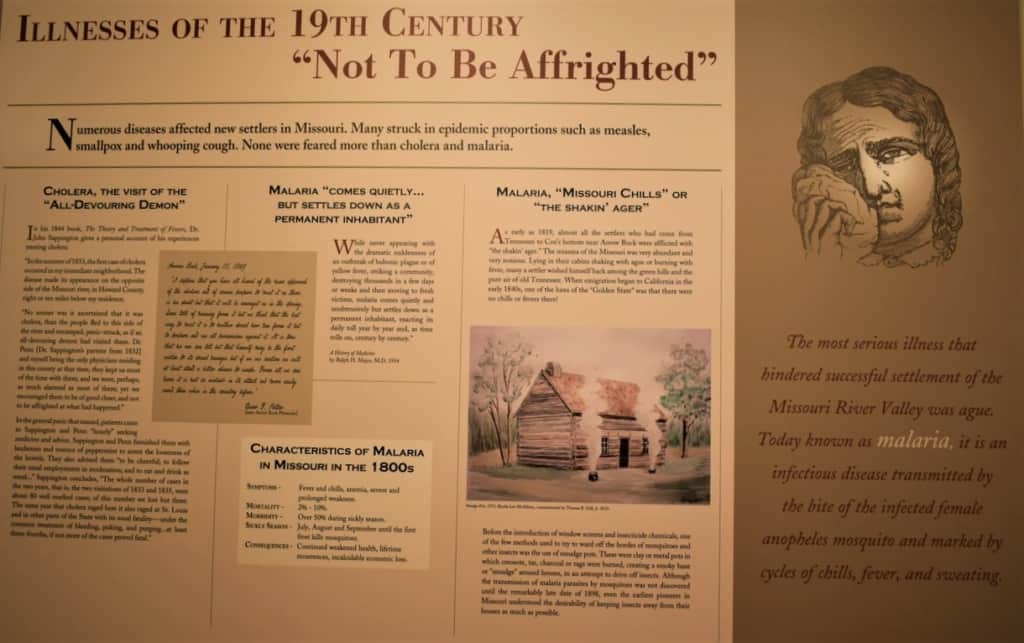

Sappington, and his family, moved to Arrow Rock in 1819. The area held much promise, as it had become well-known for its saltwater springs. This led to the nickname of Boone’s Lick, due to the Daniel Boone family building a successful salt lick operation. Dr. Sappington quickly grew in local stature not only as a physician but also as importing and exporting goods. In 1824 he partnered in a store that sold goods to travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. As the population of America migrated across the plains, diseases followed and infected many campsites.

Stopping the Spread

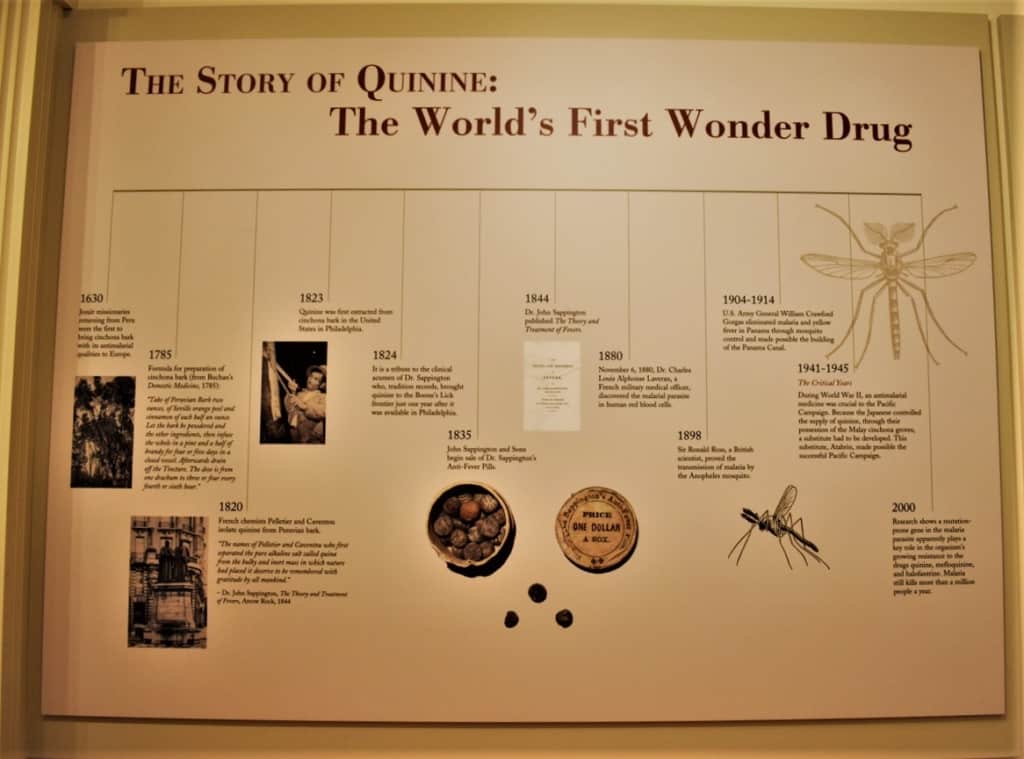

Long before Europeans visited the South American continent, the native people had already identified the healing powers of Cinchona bark. Nicknamed the “fever tree” by Spanish explorers, the bark powder would be added to water to create a powerful tonic. By the mid-1600s, this tree bark concoction was already gaining favor in treating malaria symptoms. This mosquito born disease was common in swampy or poorly drained areas. Since most pioneers chose to settle near bodies of water, malaria ravaged the frontier. Dr. Sappington discovered a way to extract the quinine from the cinchona bark and create anti-fever pills.

Taking It to Market

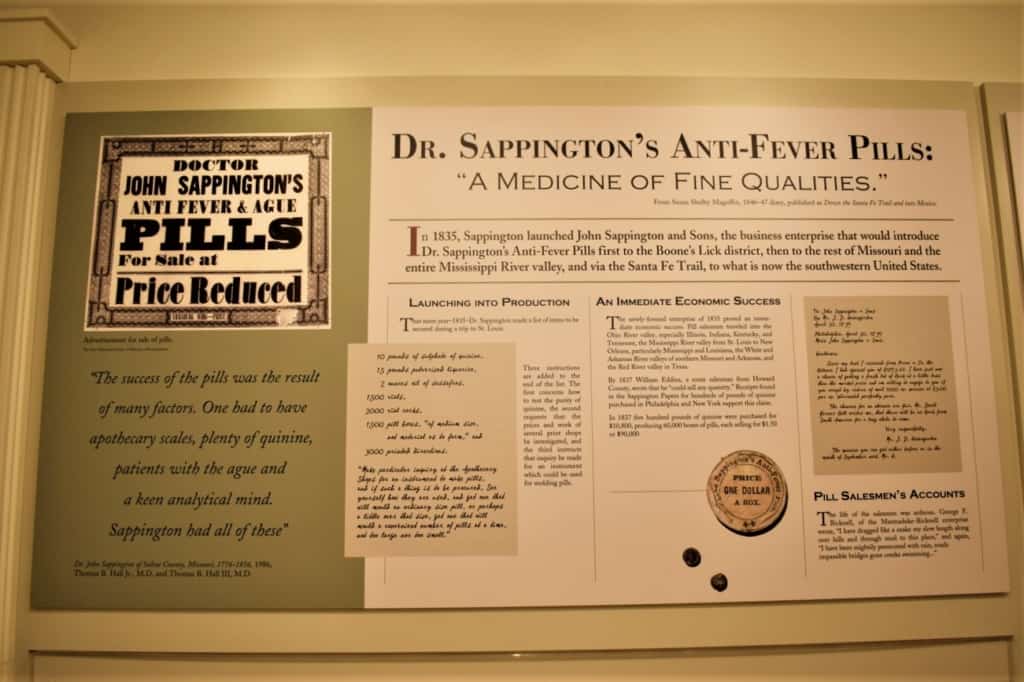

This newly developed medicine was found to cure a variety of illnesses, including influenza, scarlet and yellow fevers. Soon the pills were in high demand and Sappington created a new company to manage the sales across the continent. As the popularity of this cure spread, Sappington continued his research. He discovered that quinine pills could be used as a preventative measure to ward off malaria. Stopping the spread of this terrible disease became a primary goal for Sappington. His family and traveling sales agents regularly prescribed to this practice and were able to successfully travel safely to regions prone to malaria.

Controversy Swirls

While the success of his anti-fever pills was apparent, many in the medical field rejected their use. If the dosage was not well regulated it could result in blindness or even death. Dr. Sappington believed so strongly in sharing the success of this drug that he produced a medical book in 1844. “Theory and Treatment of Fevers” not only explained the use of the drug, it even gave the exact formula used in its manufacture. Much to his family’s dismay, this made it easy for other physicians to create their own brand of anti-fever pills.

Leaving a Legacy

Quinine remained the mainstay cure for stopping the spread of malaria into the 1940s. During World War II, Japanese forces invaded some of the regions where Cinchona trees were grown. The need for antimalarial drugs was key to the Allied forces fighting in tropical areas. A worldwide shortage created the need to speed up research into synthetic medicines. These days the use of quinine for malaria has been systematically replaced with synthetic substances that create fewer side effects. While the times have changed the use of this wonder drug, it is still amazing to discover its connection with rural Missouri. Oh, the things you learn when you head out exploring.